Off-the-Shelf (OTS) Maintenance Strategies

U.S. Department of Defense Removes Open Source Software Roadblocks (AppDev STIG)

The U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) has changed one of its key software development documents, making it even clearer that it’s okay to use open source software (OSS) in the DoD. This is good news beyond the DoD; if the US DoD can widely accept OSS, then maybe other organizations (that you deal with) can too.

That key document has the long title “Application Security & Development (AppDev) Security Technical Implementation Guide (STIG),” aka the AppDev STIG. The AppDev STIG includes some guidelines for how to write secure software, and a checklist for use before you can deploy custom software in certain cases. In the past, many people thought that using OSS in the DoD required special permission, because they misunderstood some of DoD’s policies, and this misunderstanding had crept into the AppDev STIG. The good news is that this has been fixed.

Here’s the basic background.

Open source software (OSS) is software where anyone can read, modify, and redistribute the source code (its “blueprints”) in original or modified form. OSS is widely used and developed in industry; some popular OSS includes the Linux kernel (the basis of Google’s Android), the Firefox web browser, and Apache (the world’s most popular web server). You can get quantitative numbers about OSS at http://www.dwheeler.com/oss_fs_why.html. There is a lot of high-quality OSS, and OSS is often very inexpensive even when you include installation, training, and so on.

Unfortunately, previous versions of the AppDev STIG were often interpreted as saying that using OSS required special permission. This document matters; DoD Directive (DoDD) 8500.01E requires that “all IA and IA-enabled IT products incorporated into DoD information systems shall be configured in accordance with DoD-approved security configuration guidelines” and tasks DISA to develop the STIGs. It’s often difficult to get systems fielded unless they meet the STIGs.

AppDev STIG version 3 revision 1 (an older version) said:

(APP2090.1: CAT II) “The Program Manager will obtain DAA acceptance of risk for all open source, public domain, shareware, freeware, and other software products/libraries with no warranty and no source code review capability, but are required for mission accomplishment.”

(APP2090.2: CAT II): “The Designer will document for DAA approval all open source, public domain, shareware, freeware, and other software products/libraries with limited or no warranty, but are required for mission accomplishment.”

Many people interpreted this as saying that any use of OSS required special permission. But where would the Defense Information Systems Agency (DISA), the author of the AppDev STIG, get that idea? Well, it turns out that this is a common misunderstanding of DoD policy. DoD Instruction 8500.2, February 6, 2003 has a control called “DCPD-1 Public Domain Software Controls” (http://www.dtic.mil/whs/directives/corres/pdf/850002p.pdf), which starts with this text:

Binary or machine executable public domain software products and other software products with limited or no warranty such as those commonly known as freeware or shareware are not used in DoD information systems unless they are necessary for mission accomplishment and there are no alternative IT solutions available.

A lot of people stopped reading there; they saw that “freeware” required special permission, and since OSS can often be downloaded for free, they presumed that all OSS was “freeware.” They should have kept reading, because it then goes on to make it clear that OSS is not freeware:

Such products are assessed for information assurance impacts, and approved for use by the DAA. The assessment addresses the fact that such software products are difficult or impossible to review, repair, or extend, given that the Government does not have access to the original source code and there is no owner who could make such repairs on behalf of the Government…

This latter part makes it clear that software only requires special treatment if the government cannot review, repair, or extend the software. If the government can do these things, there’s no problem, and by definition OSS provides these rights. But a lot of people didn’t understand this.

This was such a common misunderstanding that in October 2009, the DoD CIO’s memo “Clarifying Guidance Regarding Open Source Software (OSS)” specifically stated (in Attachment 2, 2c) that this was a misunderstanding (http://dodcio.defense.gov/sites/oss/2009OSS.pdf). The DoD CIO later instructed DISA to update the AppDev STIG so this misunderstanding would be removed.

The latest AppDev STIG (Version 3, Release 4) has just fixed this (http://iase.disa.mil/stigs/app_security/app_sec/app_sec.html). The new STIG:

Two related points:

But the editorial gaff in the AppDev STIG, and the work on improving the wording of controls long term, shouldn’t detract from the main point.

The main point is:

Open Source Software (OSS) is now much easier to use in the DoD.

path: /oss | Current Weblog | permanent link to this entry

I’ve learned that Open Source for America (OSFA) has awarded me a 2011 Open Source Award - Individual Award for my work to advocate consideration of “open source software in the US Department of Defense (DoD)”. They specifically point to my papers Why Open Source Software / Free Software? Look at the Numbers! and Nearly all FLOSS is Commercial.

The winners of all the 2011 awards were:

Thanks so much, OSFA! I’m honored.

path: /oss | Current Weblog | permanent link to this entry

Open Document Format 1.2 approved!

Hooray! Open Document Format for Office Applications (ODF or OpenDocument) Version 1.2 has been approved as an OASIS Standard. Finally, the world has a standard vendor-independent format for storing and exchanging ordinary office documents (particularly word processing documents, spreadsheets, and presentations) that you can edit.

Historically, people have only been able to exchange these documents if they use the same program, locking users into specific vendor products. In short, users often don’t really own the documents they create; they are often beholden to the developers of their tools. This is especially nasty for government documents; all governments have to choose some product, and whatever product they use implicitly forces their citizens to use the same product (whether they want to or not). Over time these documents can no longer be read, as products are upgraded or people change products, so this is also a disaster for archiving. We can read the Magna Carta more easily than some documents saved 30 years ago. Heck, we can read Sumerian writings more easily than some documents saved 30 years ago, and that is a scary thing. ODF provides us the possibility of actually exchanging documents, and reading archives, regardless of what program was used to create them. In short, people now have real freedom when they create and exchange normal office documents — they are no longer locked into a particular supplier or version of program.

Rob Weir has some of the highlights of version 1.2, and he has also written an overview of ODF.

For me, the highlight is OpenFormula. Previous versions of the specification could exchange spreadsheets, but did not standardize the format of recalculated formulas. I led the subcommittee in the ODF Technical Committee to nail down exactly how to recalculate formulas. The result: We now have a real spec. My sincere thanks to the many who helped make this possible. Feel free to see my 2011-05-28 post about the success of OpenFormula.

I’m sure that there will continue to be refinements for years to come; that is normal for a standard. In some sense this is after the fact; like many good standards, it was developed through the cooperation of many of the implementors. It is already implemented, at least in part, in many places, and I expect even more completed implementations soon.

The key, though, is that users can finally own the documents they create. That is a major step forward, for all of us.

path: /oss | Current Weblog | permanent link to this entry

Petition the White House to cease issuing software patents

I encourage all US citizens to sign this petition to the US White House to “direct the patent office to cease issuing software patents”. I believe software patents impede innovation (instead of helping it), and they have become a threat to the US economy. Many organizations involved in software are now spending lots of time fending off patent trolls, fighting patent lawsuits, or cannot safely solve problems due to patent thickets. The recently-passed “America Invents Act” (AIA) completely failed to deal with this fundamental problem.

Signing a petition won’t immediately solve anything. That’s not how it works. But repeatedly making the government aware that there’s a real problem is a good first step to solving a problem. In the US, the right of the people to petition their government is guaranteed by the first amendment of the US Constitution (“Congress shall make no law …. abridging… the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances”). Everyone is affected today by software, and so far the government has not effectively dealt with the problem. Please use this opportunity to make the government aware of a real problem.

path: /oss | Current Weblog | permanent link to this entry

Off-the-Shelf (OTS) Software Maintenance Strategies

Off-the-shelf (OTS) software is simply software that is ready-made and available for use. Even when you need a custom system, building it from many OTS components has many advantages, which is why everyone does it. OTS works because you can save money and time, increase quality, and increase innovation through resource pooling.

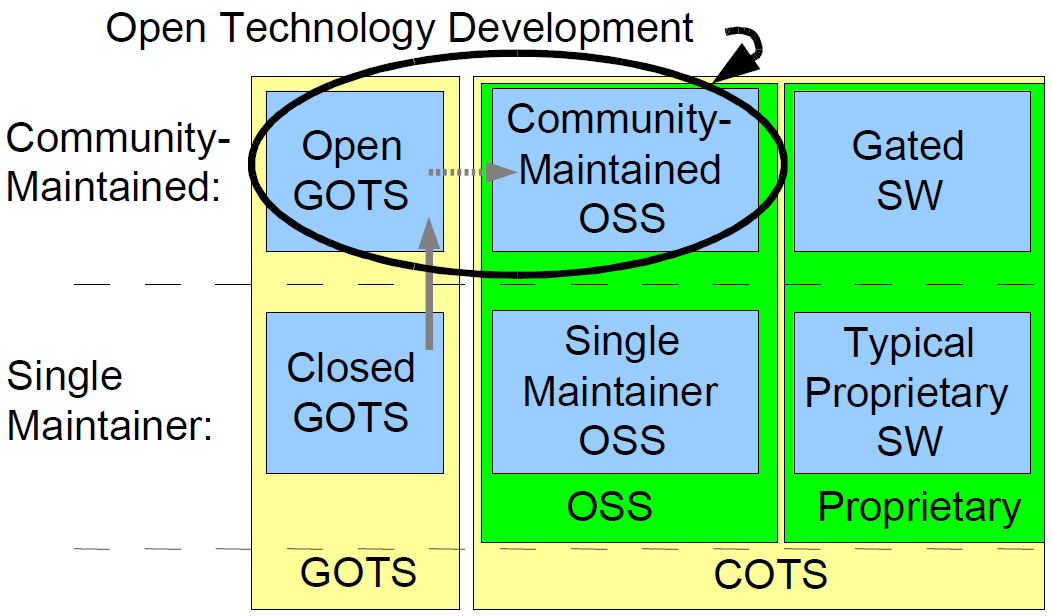

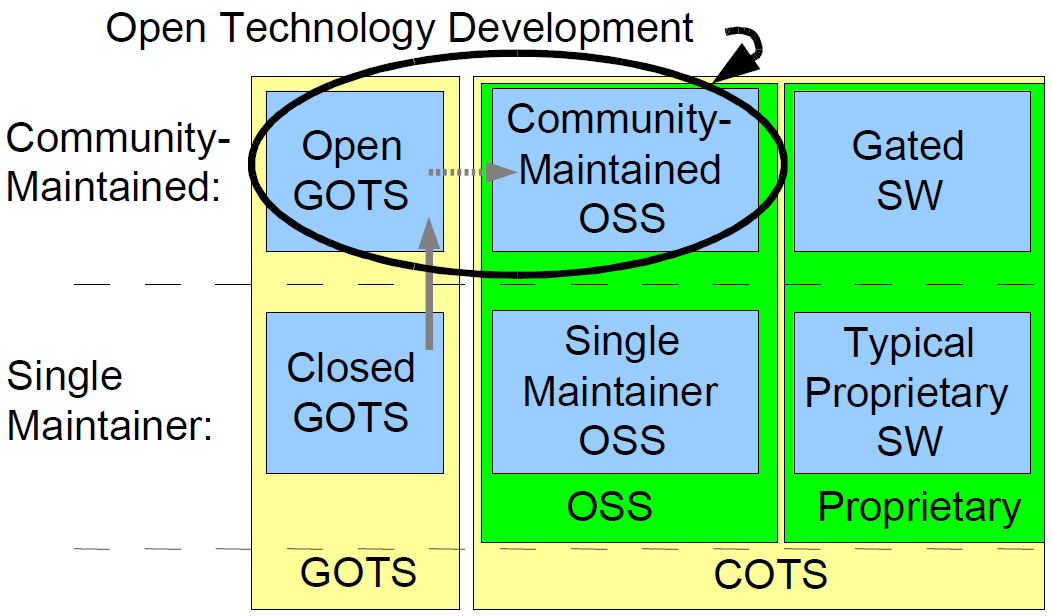

However, people can get easily confused by the many different ways that off-the-shelf (OTS) software can be maintained. Terminology varies, and there hasn’t been an obvious way to describe how these different approaches are related. In 2010 I chatted with several others about how to make this clearer, and then created a picture that I think clarifies things. My thanks to helpful critiques from Heather Burke and John Scott. So here’s the picture, followed by a discussion on what it means.

If OTS software is commercial, it’s commercial OTS (COTS) software. By U.S. law, any software is commercial if it is (1) sold, licensed, or leased to the public, and (2) has a non-governmental use. There are two kinds of COTS software: Open Source Software (OSS) and proprietary software. OSS, put briefly, is software whose licenses give users the freedom to run the program for any purpose, to study and modify the program, and to redistribute copies of either the original or modified program (without having to pay royalties to previous developers). Yes, practically all OSS is commercial.

OTS can also be retained and maintained internally by an organization. For example, the U.S. government develops and maintains some software internally. In the U.S. government world, such software often called government OTS (GOTS). This figure shows things from the point of view of the U.S. government, but if you work with some other organization, you can think of this figure with your organization in the place of the U.S. government. (Maybe this should be called “internal off-the-shelf” or “IOTS” instead!) The idea here is that any organization can have software that it controls internally, and view as internal OTS software, as well as the COTS software that is available to the public.

There are various reasons why the government should sometimes keep certain software in-house, e.g., because sole possession of the software gives the U.S. a distinct advantage over its adversaries. However, there is also considerable risk to the government if it tries to privately hold GOTS software within the government for too long. Technological advantage is usually fleeting. Often there is a commercially-developed item available to the public that begins to perform similar functions. As it matures, other organizations begin using this non-GOTS solution, potentially rendering the GOTS solution obsolete. Such cases often impose difficult decisions, as the government must determine if it will pay the heavy asymmetrical cost to switch, or if it will continue “as usual” with its now-obsolete GOTS systems (with high annual costs and limitations that may risk lives or missions).

Either COTS or GOTS may be maintained by a single maintainer or by a community. In community maintenance there is often a single organization who determines if proposals should be accepted, but the key here is that the work tends to be distributed among those affected. An Open GOTS (OGOTS) project is a GOTS project which uses multiple-organization collaborative development approaches to develop and maintain software, in a manner similar to OSS. Some people use the term “Government Open Source Software” (GOSS) instead of OGOTS (in particular, GOSS for Govies uses the term GOSS instead).

GOTS (including OGOTS) is basically a special case of “gated software” with development inside a government. However, governments are bigger than most companies, and (in democracies) they are supposed to serve all of their citizenry, and those factors make them rather different than most other gated communities. Community development of proprietary software (“gated software”) outside governments is less common, but it can happen (historically some parts of Unix were developed this way). The term Open Technology Development (OTD) involves community development among government users (in the case of government developers), and thus it includes both OSS and OGOTS (aka GOSS).

I should note that I have a broad view of maintenance. I’ve often said that there is only one program — “Hello, World” — and that the rest is maintenance. That’s overstated for effect, but I believe there is a lot of truth in that statement.

This figure, and some of the text above, is in section 1.3 of the paper Open Technology Development (OTD): Lessons Learned & Best Practices for Military Software (also available via MIL-OSS), which is released under the Creative Commons BY-SA license. If you’re interested in more, please see the paper! The figure and some of the text are also part of “Software is a Renewable Military Resource” by John Scott, Dr. David A. Wheeler, Mark Lucas, and J.C. Herz, Journal of Software Technology, February 2011, Vol. 14, Number 1.

I hope this figure makes it easier to understand the different approaches for maintaining off-the-shelf (OTS) software.

path: /oss | Current Weblog | permanent link to this entry

Ask not who holds the copyrights

Asking “who has the copyright?” for intellectual works (like software, documents, and data) is almost always the wrong question to ask. Instead, ask “what rights do I have (or can I get)?” and “do those rights let me do what I want to do?”. In a vast number of situations, those are the right questions to ask instead. Even people who should know better can fall into this subtle trap!

This became obvious to me when it was revealed that even the smart people at the Apache Software Foundation fell into this. In the recent Accumulo proposal, there were unnecessary copyright hurdles because Apache was unnecessarily asking for a copyright transfer, instead of the necessary rights (in this case, there was no copyright to transfer!).

So I’ve justed posted Ask Not Who Holds the Copyright, which I hope will clear this up.

path: /oss | Current Weblog | permanent link to this entry

I recently went to the MIL-OSS

(“military open source software”)

2011 Working Group (WG) /

Conference in Atlanta, Georgia.

Topics included the open prosthetics project,

releasing government-funded software as OSS,

replacing MATLAB with Python,

the “Open Technology Dossier Protocol” (OTDP),

confining users using SELinux,

an explanation of DoD policies on OSS,

Charlie Schweik’s study on what makes a success OSS project,

and more.

Some people started developing a walkie-talkie Android app at the conference.

Here’s a summary of the conference, if you’re curious.

I recently went to the MIL-OSS

(“military open source software”)

2011 Working Group (WG) /

Conference in Atlanta, Georgia.

Topics included the open prosthetics project,

releasing government-funded software as OSS,

replacing MATLAB with Python,

the “Open Technology Dossier Protocol” (OTDP),

confining users using SELinux,

an explanation of DoD policies on OSS,

Charlie Schweik’s study on what makes a success OSS project,

and more.

Some people started developing a walkie-talkie Android app at the conference.

Here’s a summary of the conference, if you’re curious.

First, a few general comments. If this conference is any guide, it is slowly getting easier to get OSS into government (including military) systems. OSS is already used in many places, but it’s often “don’t ask, don’t tell”, and there are still lots of silly bureaucratic barriers that prevent the use of OSS where it should be used or at least considered. But there were many success stories, with slide titles like “how we succeeded”.

Although the conference had serious purposes, it was all done in good humor. All participants got the MIL-OSS poster of Uncle Sam (saying “I want YOU to Open Source!”). The theme of the conference was the WarGames movie; the first finder for each of the WarGames Easter eggs would get a silly 80s-style prize (such as an Atari T-shirt).

As the MIL-OSS 2011 presentations list shows, I gave three talks:

The conference was complicated by the recent passing of Hurricane Irene. The area itself was fine, but some people had trouble flying in. The first day’s whole schedule was delayed so speakers could arrive (using rescheduled flights). That was probably the best thing to do in the circumstance — it was basically like a temporary time zone change — but it meant that one of my talks that day (Why the GPL Might not Destroy the Universe) was at 9:10pm. And I wasn’t even the last speaker. Eeeek. Around 15 speakers had still not arrived when the conference arrived, but all but one managed to get there before they had to speak.

Here are few notes on the talks:

Many discussions revolved around the problems of getting authentication/authorization working without passwords, in particular using the ID cards now widely used by nearly all western governments (such as DoD CAC cards). Although things can work sometimes, it’s incredibly painful to get them to work on any system (OSS or not), and they are fragile. Dmitri Pal (Red Hat)’s talk “CAC and Kerberos From Vision to Reality” discussed some of the problems and ways to possibly make it better. The OpenSSH developers are actively hostile to the X.509 standard that everyone uses for identity certificates; I agree with the OpenSSH folks that X.509 is clunky, but that is what everyone uses, and not supporting X.509 means that openssh is useless for them. Every card reader is incompatible with the others, so every time a new model comes out, drivers have to be written and it often doesn’t work anyway (compare that to USB keyboards, which “just work” every time even through KVM switches). I think some group needs to be formed, maybe a “Simple Authorization without passwords” group, with the goal of setting standards and building OSS components so that systems by default (maybe by installing one package) can trivially use PKI and other systems and have it “just work” every time. No matter that client, server (relying party), or third-party authenticator/authorization server is in use.

If you’re interested in more of my personal thoughts about OSS and the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD), also see FLOSS Weekly #160, the interview of David A. Wheeler by Randal Schwartz and Simon Phipps. Good general sites for more info are the MIL-OSS website and the DoD CIO Free Open Source Software (FOSS) site.

There’s more to be done, but a lot is already happening.

path: /oss | Current Weblog | permanent link to this entry

GNOME 3 Shell is terrible, I am switching to XFCE

I’m a long-time user of Fedora and GNOME. GNOME 2 has served me well over the years, so I was interested in what the GNOME people were cooking for GNOME 3. Fedora 15 comes with the new GNOME 3 shell; since change can sometimes be good, I’ve tried to give the new GNOME 3 shell a fair trial.

But after giving GNOME 3 (especially GNOME shell) some time, I’ve decided that I hate the GNOME 3 shell as it’s currently implemented. It’s not just me; the list of people who have complaints about the GNOME 3 shell include Linus Torvalds, Dedoimedo (see also here), k3rnel.net (Juan “Nushio” Rodriguez), Martin Sourada, junger95, and others. LWN noted the problems of GNOME 3 shell way back. So many people are leaving GNOME 3, often moving to XFCE, that one person posted a poem titled “GNOME 3, Unity, and XFCE: The Mass Exodus”.

The GNOME 3 shell is beautiful. No doubt. But as far as I can tell, the developers concentrated on making it beautiful, cool and different, but as a consequence made it far less useful and efficient for people. Dedoimedo summarizes GNOME 3.0 shell as, “While it’s a very pretty and comely interface, it struck me as counterproductive, designed with a change for the sake of change.” In a different post Dedoimedo says, “Gnome 3 is a toy. A beautiful, aesthetic toy. But it is not a productivity item… I am not a child. My computer is not a toy. It’s a serious tool… Don’t mistake conservative for inefficient. I just want my efficiency.”.

Some developers have tried to fix its worst problems of GNOME 3 shell with extensions, and if GNOME developers work at it, I think they could change it into something useful. But most of these problems aren’t just maturity issues; GNOME 3 shell is broken by design. So I’m going to switch to XFCE so I can get work done, and perhaps try it again later if they’ve started to fix it. Thankfully, Fedora 15 makes it easy to switch to another desktop like XFCE, so I can keep on happily using Fedora.

So what’s wrong?

I’ve been trying to figure out why I hate GNOME 3 so much, and it comes down to two issues: (1) GNOME 3’s shell makes it much harder to do simple, common tasks, and (2) GNOME 3 shell often hides how to do tasks (it’s not “discoverable”). These are not just my opinions, lots of people say these kinds of things. k3rnel.net says, “Gnome’s ‘Simplicity’ is down right insulting to a computer enthusiast. It makes it impossible to do simple tasks that used to flow naturally, and it’s made dozens of bizarre ‘design decisions’, like hiding Power Off behind the ‘Alt’ key.” Let me give you examples of each of these issues.

First of all, GNOME 3 (particularly its default GNOME shell) creates a lot of extra steps and work to do simple tasks that used to be simpler. To run a program whose name you don’t know, you have go to the far top left to the hot spot (or press “LOGO”), move your mouse to the hideously hard-to-place (and not obvious) “Applications” word slightly down the right, then mouse to the far right to choose a category, then mouse back to choose it. That’s absurd; the corners of the screen are especially easy to get to, and they fail to use that fact when choosing non-favorite applications. Remarkably, there doesn’t seem to be a quick way to simply show the list of (organized) applications you can start; there’s not even a keyboard shortcut for “LOGO Applications”. Eek. This is a basic item; even Windows 95 was easier. Would it really have killed anyone to make moving to some other area (say, the bottom left corner) show the applications? And why are the categories on the far right, where they are least easy to get to and not where any other system puts them? (Yes, the favorites area lets you start some programs, but you have to find it the first time, and some of us use many programs.) Also, you can’t quickly alt-tab between arbitrary windows (Alt-tab only moves between apps, and the undiscoverable alt-` only moves between windows of the same app). GNOME shell makes it easy to do instant messaging, but it makes it harder to do everything else. Fail.

GNOME 3’s capabilities are not discoverable, either. To log off or change system settings you click on your name — and that’s already non-obvious. But it gets worse. To power off, you click on your name, then press the ALT key to display the power off option, then select it. How the heck would a normal user find out about this? The only obvious way to power down the system is to log out, then power off from the front. If you know an application name, pressing LOGO (aka WINDOWS) and typing its name is actually a nice feature, but that is not discoverable either. If you want a new process or window (like a new terminal window or file manager window), you have to know press control when you select its icon to start a new process (for Terminal, you can also start it and press shift+control+N, but that is not true for all programs). The need to press control isn’t discoverable (it’s also a terrible default; if I press a program icon, I want a new one; if I wanted an existing one I’d select its window instead). Fail.

There are some nice things about GNOME 3 shell. As I mentioned earlier, I like the ability to press LOGO start typing a program name (which you can then select) - that is nice. But even then, this is not discoverable; how would a user new to the interface know that they should press the LOGO button? This functionality is trivial to get in other desktop environments; I configured XFCE to provide the same functionality in less than a minute (in a way that is less pretty, but much easier for a human to use).

The implementors seem to think that new is automatically better. Rediculous. I don’t use computers to have the newest fad interface, I use them to get things done (and for the pleasure of using them). I will accept changes, but they should be obvious improvements. Every change just for its own sake imposes relearning costs, especially for people like me who use many different computers and interfaces, and especially if they make common operations harder. Non-discoverability is especially nasty; people don’t want to read manuals for basic GUI interfaces, they want to get things done.

I don’t think GNOME 3 is mature, either. For example, as of 2011-07-28, GNOME 3 does not support screensavers — it just shows a blank screen after a timeout. But the previous GNOME 2 had screensavers. Heck, Windows 3.0 (of 1993) did better than that; it had screensavers, and I’m sure there were screensavers before then.

I’ve tried to get used to it, because I wanted to give new ideas a chance. Different can be better! But so far, I’m not impressed. The code may be cleaner, and it may be pretty, but the user experience is currently lousy.

If you’re stuck using the GNOME 3 Shell, you basically must read the GNOME shell cheat sheet, because so much of what it does is un-intuitive, incompatible with everything else, and non-discoverable. Needing to read a manual to use a modern user interface is not a good sign.

You could try switching to the GNOME 3 fallback mode, as discussed by Dedoimedo and others. This turns on a more tradtional interface. Several people have declared that GNOME 3 fallback is better than GNOME shell itself. But I was not pleased; it’s not really well-supported, and it’s really not clear that this will be supported long term.

You can also try various tweaks, configurations, and additional packages to make GNOME 3 shell more tolerable. If you’re stuck with GNOME 3 shell, install and use gnome-tweak-tool; that helps. You should also install the Fedora gnome-shell-extensions-alternative-status-menu package, which lets you see “Power off” as an option.

But after trying all that, I decided that it’d be better to switch to another more productive and mature desktop environment. Obvious options are XFCE and KDE.

XFCE is a lightweight desktop environment, and is what I’ve chosen to use instead of the default GNOME 3 shell. I found out later that other people have switched to XFCE after trying and hating GNOME 3’s shell. XFCE doesn’t look as nice as GNOME 3, indeed, the GNOME 3 shell is really quite flashy by comparison. But the GNOME shell makes it hard for me to get anything done, and that’s more important.

I expect that it wouldn’t be hard for the developers to make it better; hopefully the GNOME folks will work to improve it. If many of GNOME 3’s problems are fixed, then I’ll be happy to try it again. But I’m in no hurry; XFCE works just fine.

I’m creating a new page on my website called Notes on Fedora so that I can record “how to” stuff, in case that others find it useful. For example, I’ve recorded how to turn on some stuff in XFCE to make it prettier. Enjoy!

path: /oss | Current Weblog | permanent link to this entry

Upcoming FLOSS in Government Conferences for 2011

If you’re interested in free/libre/open source software in government (particularly the U.S. federal government), there are two upcoming conferences you should consider.

One is Government Open Source Conference (GOSCON) 2011 on August 23, 2011. It will be held at the Washington Convention Center, Washington, DC.

The other is the Military Open Source Software (MIL-OSS) WG3 conference on August 30 - September 1, 2011. It will be held in Atlanta, Georgia.

I’ll be speaking at both. But don’t let that dissuade you :-).

path: /oss | Current Weblog | permanent link to this entry

Microsoft, co-author of the Linux kernel

Truth is often stranger than fiction. Microsoft was the fifth-largest corporate contributor to the Linux kernel version 3.0.0, as measured by the number of changes to its previous release. Only Red Hat, Intel, Novell, and IBM had more contributions. Microsoft was #15 as measured by number of lines changed, which is smaller but is still an impressively large number.

This work by Microsoft was to clean up the “Microsoft Hyper-V (HV) driver” so that the Microsoft driver would be included in the mainline Linux kernel. Microsoft originally submitted this set of code changes back in July 2009, but there were a lot of problems with it, and the Linux kernel developers insisted that it be fixed. The Linux community had a long list of issues with Microsoft’s code, but the good news is that Microsoft worked to improve the quality of its code so that it could be accepted into the Linux kernel. Other developers helped Microsoft get their code up to par, too. ( Steve Friedl has some comments about its early technical issues.) There’s something rather amusing about watching Microsoft (a company that focuses on software development) being forced by the Linux community to improve the quality of Microsoft’s code. Anyone who thinks that FLOSS projects (which typically use widespread public peer review) always produce lower quality software than proprietary vendors just isn’t watching the real world (see my survey paper of quantitative FLOSS studies if you want more on that point). Peer review often exposes problems, so that they can be fixed, and that is what happened here.

Microsoft did not do this for the sheer thrill of it. Getting code into the mainline Linux kernel release, instead of just existing as a separate patch, is vitally important for an organization if they want people to use their software (if it needs to be part of the Linux kernel, as this did). A counter-example is that the Xen developers let KVM zoom ahead of them, because the Xen developers failed to set a high priority on getting full support for Xen into the mainline Linux kernel. As Thorsten Leemhuis at The H says, “There are many indications that the Xen developers should have put more effort into merging Xen support into the official kernel earlier. After all, while Xen was giving developers and distribution users a hard time with the old kernel, a new virtualisation star was rising on the open source horizon: KVM (Kernel-based Virtual Machine)… In the beginning, KVM could not touch the functional scope and speed of Xen. But soon, open source developers, Linux distributors, and companies such as AMD, Intel and IBM became interested in KVM and contributed a number of improvements, so that KVM quickly caught up and even moved past Xen in some respects.” Xen may do well in the future, but this is still a cautionary tale.

This doesn’t mean that Microsoft is suddenly releasing all its programs as free/libre/open source software (FLOSS). Far from it. It is obvious to me that Microsoft is contributing this code for the same reason many companies contribute to the Linux kernel and other FLOSS software projects: Money.

I think it is clear that Microsoft hopes that these changes to Linux will help Microsoft sell more Windows licenses. These changes enable Linux to run much better (e.g., more efficiently) on top of Microsoft Windows’ hypervisor (Hyper-V). Without them, people who want to run Linux on top of a hypervisor are much more likely to use products other than Microsoft’s. Microsoft doesn’t want to be at a competitive disadvantage in this market, so to sell its product, it chose to contribute changes to the Linux kernel. With this change, Microsoft Windows becomes a more viable option as a host operating system, running Linux as a guest.

Is this a big change? In some ways it is not. Microsoft has developed a number of FLOSS packages, such as WiX (for installing software on Windows), and it does all it can to encourage the development of FLOSS that run on Windows.

Still, it’s something of a change for Microsoft. Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer stated in 2001 that Linux and the GNU GPL license were “a cancer”. This was in many ways an attack on FLOSS in general; the GNU GPL is the most popular FLOSS license by far, and a MITRE report found that the “GPL sufficiently dominates in DoD applications for a ban on GPL to closely approximate a full ban of all [FLOSS]”. This would have been disastrous for their customer, because MITRE found that FLOSS software “plays a far more critical role in the [Department of Defense] than has been generally recognized”. I think many other organizations would say the same. This is not even the first time Microsoft has gotten involved with the GPL. Microsoft sold Windows Services for Unix (SFU), which had GPL software, showing that even Microsoft understood that it was possible to make money while using the GPL license. But this more case is far more extreme; in this case Microsoft is actively helping a product (the Linux kernel) that it also competes with. I don’t expect Microsoft to keep contributing significantly to the Linux kernel, at least for a while, but that doesn’t matter; here we see that cash trumps ideology. More generally, this beautifully illustrates collaborative development: Anyone can choose to work on specific areas of a FLOSS program, for their own specific or selfish reasons, to co-produce works that help us all.

path: /oss | Current Weblog | permanent link to this entry

U.S. government must balance its budget

(This is a blog entry for U.S. citizens — everyone else can ignore it.)

We Americans must demand that the U.S. government work to balance its budget over time. The U.S. government has a massive annual deficit, resulting in a massive national debt that is growing beyond all reasonable bounds. For example, in just Fiscal Year (FY) 2010, about $3.4 trillion was spent, but only $2.1 trillion was received; that means that the U.S. government spent more than a trillion dollars more than it received. Every year that the government spends more than it receives it adds to the gross federal debt, which is now more than $13.6 trillion.

This is unsustainable. The fact that this is unsustainable is certainly not news. The U.S. Financial Condition and Fiscal Future Briefing (GAO, 2008) says, bluntly, that the “Current Fiscal Policy Is Unsustainable”. “The Moment of Truth: Report of the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform” similarly says “Our nation is on an unsustainable fiscal path”. Many others have said the same. But even though it’s not news, it needs to be yelled from the rooftops.

The fundamental problem is that too many Americans — aka “we the people” — have not (so far) been willing to face this unpleasant fact. Fareed Zakaria nicely put this in February 21, 2010: “ … in one sense, Washington is delivering to the American people exactly what they seem to want. In poll after poll, we find that the public is generally opposed to any new taxes, but we also discover that the public will immediately punish anyone who proposes spending cuts in any middle class program which are the ones where the money is in the federal budget. Now, there is only one way to square this circle short of magic, and that is to borrow money, and that is what we have done for decades now at the local, state and federal level … The lesson of the polls in the recent elections is that politicians will succeed if they pander to this public schizophrenia. So, the next time you accuse Washington of being irresponsible, save some of that blame for yourself and your friends”.

But Americans must face the fact that we must balance the budget. And we must face it now. We must balance the budget the same way families balance their budgets — the government must raise income (taxes), lower expenditures (government spending), or both. Growth over time will not fix the problem.

How we rellocate income and outgo so that they match needs to be a political process. Working out compromises is what the political process is supposed to be all about; nobody gets everything they want, but eventually some sort of rough set of priorities must be worked out for the resources available. Compromise is not a dirty word to describe the job of politics; it is the job. In reality, I think we will need to both raise revenue and decrease spending. I think we must raise taxes to some small degree, but we can’t raise taxes on the lower or middle class much; they don’t have the money. Also, we will not be able to solve this by taxing the rich out of the country. Which means that we must cut spending somehow. Just cutting defense spending won’t work; defense is only 20% of the entire budget. In contrast, the so-called entitlements — mainly medicare, medicaid, and social security — are 43% of the government costs and rapidly growing in cost. I think we are going to have to lower entitlement spending; that is undesirable, but we can’t keep providing services we can’t pay for. The alternative is to dramatically increase taxes to pay for them, and I do not think that will work. Raising the age before Social Security benefits can normally be received is to me an obvious baby step, but again, that alone will not solve the problem. It’s clearly possible to hammer out approaches to make this work, as long as the various camps are willing to work out a compromise.

To get there, we need to specify and plan out the maximum debt that the U.S. will incur in each year, decreasing that each year (say, over a 10-year period). Then Congress (and the President) will need to work out, each year, how to meet that requirement. It doesn’t need to be any of the plans that have been put forward so far; there are lots of ways to do this. But unless we agree that we must live within our means, we will not be able to make the decisions necessary to do so. The U.S. is not a Greece, at least not now, but we must make decisions soon to prevent bad results. I am posting this on Independence Day; Americans have been willing to undergo lots of suffering to gain control over their destinies, and I think they are still able to do so today.

In the short term (say a year), I suspect we will need to focus on short-term recovery rather than balancing the budget. And we must not default. But we must set the plans in motion to stop the runaway deficit, and get that budget balanced. The only way to get there is for the citizenry to demand it stop, before far worse things happen.

path: /misc | Current Weblog | permanent link to this entry

After years of work, the world is making a step forward to letting authors own and control their own documents, instead of having them controlled by office document software vendors.

Historically, every office document suite has stored data in its own incompatible format, locking users into that suite and inhibiting competition. This lack of a free and open office document format also makes a lie out of archiving; storing the bits is irrelevant because formats change over time in undocumented ways, with the result that later programs often cannot read older files (we can still read the Magna Carta, but some powerpoint files I created only 15 years ago cannot be read by current versions of Microsoft Office). Governments in particular should not have their documents beholden to any supplier; important government documents should be available to future generations.

Thankfully, the OASIS Open Document Format for Office Applications (OpenDocument) Technical Committee (TC) is wrapping up its update of the OpenDocument standard, and I think they are about to complete the new version 1.2. This standard lets people store and exchange editable office documents so they edited by programs made by different suppliers. This will enable real competition, and enable future generations to read the materials we develop today. The TC has already approved OpenDocument v1.2 as a Committee Specification, and at this point I think the odds are excellent that it will get through the rest of the process and become formally approved.

One of the big improvements, from my point of view, is that the TC has successfully defined how to store and exchange recalculated formulas in office documents. That was my goal for joining the TC years ago, and I’m delighted to have played a part in this update. Since it looks like it’s on its way to success, I plan to step down as chair of the OASIS Office formula subcommittee and to leave the TC. I am very grateful to everyone who helped — thank you. For those who aren’t familiar with the story of the formula subcommittee, please let me give a brief background.

Years ago I was delighted to see a standard way to store office documents and exchange them between different suppliers’ products: OASIS Open Document Format for Office Applications (OpenDocument). People around the world create office documents, so this is a standard the world really needed!! However, I was deeply troubled when I discovered that this specification did not include a standard way to exchange recalculated formulas, such as those used in spreadsheets. I thought this was an important weakness in the specification. So I talked to others to see what could be done, and started work that might fill this void, including recruiting people to help.

I am delighted to report that we now have a specification for formulas: OpenFormula, part 2 of the current draft of the OpenDocument standard. Now the world has a standard, developed by multiple suppliers, that lets people store office documents for future generations and exchange office documents between different suppliers’ products, that includes recalculated formulas. And it’s not just a spec; people are already implementing it (which is good; only implemented specs have value). There are still some procedural steps, but I have high hopes that at this point we are essentially done.

This work was not done by just me, of course, or even primarily by me. A vast number of people worked directly and behind the scenes to make it happen. I cannot possibly list them all. I can, however, express my great gratitude to them. Thank you, thank you, thank you. You — and there are many of you — have made this a success. Again, thank you so very much.

The reason I joined the OASIS technical committee (TC) was to help create this formula specification and turn it into a reality. Making a real standard, one agreed on by multiple parties, takes a lot of work. We developers of the formula specification discussed details such as what 0 to the 0 power should mean, date basis systems, unit systems, and many other details like that, because addressing detailed issues is necessary to create a good standard. We had to nail down evaluation order and determine that a light-year is the distance light travels in exactly 365.25 days. And so on. We got a lot of participation by various spreadsheet suppliers; implementers even changed their implementations to conform with the draft spec as it was being developed! This work took time, but the point was to create a specification people would actually use, not just put on a shelf, and that made the extra time worth it. If you are interested in learning more, feel free to listen to The ODF Podcast 004: David A. Wheeler on OpenFormula (an interview of me by Rob Weir).

Now, finally, that work appears to be done. As I noted, there are a few procedural steps before the current specification becomes an official standard; change is always possible. Also, I’m sure there will be clarifications and additions over time, as with any standard in use. But at this point, I think my goal has been accomplished, and I am grateful.

So, I think now is a good time for me to make a graceful exit from the TC. After all, my goal has been accomplished. So, I intend to step down as subcommittee chair of the formula subcommittee and to leave the TC. Technically there are still some procedural steps and there’s a potential for issues; if there’s a need for me help to wrap up something, I’ll do so. But I think things are concluding, so it’s a good time to say so.

I think the effort to specify spreadsheet formulas has been a great success. We got a lot accomplished. Most importantly, we got something important accomplished for the world. Thank you, everyone who helped.

path: /oss | Current Weblog | permanent link to this entry

I’ve made various updates to my list of The Most Important Software Innovations. I’ve added Distributed Version Control System (DVCS); these are all over now in the form of git, Mercurial (hg), Bazaar, Monotone, and so on, but these were influenced by the earlier BitKeeper, which was in turn influenced by the earlier Teamware (developed by Sun starting in 1991). As is often the case, “new” innovations are actually much older than people realize. I also added make, originally developed in 1977, and quicksort, developed in 1960-1961 by C.A.R. (Tony) Hoare. I’ve also improved lots of material that was already there, such as a better description of the history of the remote procedure call (RPC).

So please enjoy The Most Important Software Innovations!

path: /misc | Current Weblog | permanent link to this entry

Comparing Free/Libre/Open Source Software (FLOSS) with Charles River Bridge vs. Warren Bridge

I’ve been reading over an old court case and thinking about how it relates to the issue of government releasing free / libre / open source software (FLOSS). The case is Charles River Bridge v. Warren Bridge, 36 U.S. 420, including the final U.S. Supreme Court decision (United States Supreme Court reports, Vol. 9 (PDF page 773 on)). This is old; the decision was rendered in 1837. But I think it has interesting ramifications for today.

Any lawyer will correctly tell you that you must not look at one court decision to answer a specific question. And any lawyer will tell you that the details matter; a case with different facts may have a different ruling. Fine. I’m not a lawyer anyway, and I am not trying to create a formal legal opinion (this is a blog, not a legal opinion!). But still, it’s useful to look at these pivotal cases and try to think about their wider implications. I think we should all think about what’s good (or not good) for our communities, and how we should help our governments enable that; that is not a domain exclusive to lawyers.

So, what was this case all about? Wikipedia has a nice summary. Basically, in 1785 the Charles River Bridge Company was granted a charter to construct a bridge over the Charles River between Boston and Charleston. The bridge owners got quite wealthy from the bridge tolls, but the public was not so happy with having to keep paying and paying for such a key service. So Massachusetts allowed another company to build another bridge, the Warren bridge, next to the original Charles River bridge. What’s more, this second agreement stipulated that the Warren bridge would, after a certain time, be turned over to the state and be free for the public to use. The Charles River bridge owners were enraged — they knew that a free-to-use bridge would eliminate their profits. So they sued.

As noted in Wikipedia, the majority decision (read by Taney) was that any charter contract should be interpreted as narrowly as possible. Since the Charles River Bridge contract did not explicitly guarantee exclusive rights, the Supreme Court held that they didn’t get exclusive rights. The Supreme Court also determined that, in general, public grants should be interpreted closely and if there is ever any uncertainty in a contract, the decision made should be one to better the public. Taney said, “While the rights of private property are sacredly guarded, we must not forget that the community also have rights, and that the happiness and well-being of every citizen depends on their faithful preservation.” In his remarks, Taney also explored what the negative effects on the country would be if the Court had sided with the Charles River Bridge Company. He stated that had that been the decision of the Court, transportation would be affected around the whole country. Taney made the point that with the rise of technology, canals and railroads had started to take away business from highways, and if charters granted monopolies to corporations, then these sorts of transportation improvements would not be able to flourish. If this were the case then, Taney said, the country would “be thrown back to the improvements of the last century, and obliged to stand still.”

So how does this relate to FLOSS and government? Well first, let me set the stage, by pulling in a different strand of thought. The U.S. government pays to develop a lot of software. I think that in general, when “we the people” pay for software, then “we the people” should get it. The idea of paying for some software to be developed, and then giving long monopoly rights to a single company, seems to fly in the face of this. It doesn’t make sense from a cost viewpoint; when there’s a single monopoly supplier, the costs go up because there’s no effective competition! Some software shouldn’t be released to the public at all, but that is what classification and export controls are supposed to deal with. I’m sure there are exceptions, but currently we assume that when “we the people” pay to develop software, then “we the people” do not get the software, and that is absurd. If someone wants to have exclusive rights to some software, then he should spend all his time and money to develop it.

A fair retort to my argument is, “But does the government have the right to take an action that might put reduce the profits of a business, or put it out of business?” In particular, if the government paid to develop software, can the government release that software as FLOSS if a private company sells equivalent proprietary software? After all, that private company would suddenly find itself competing with a less-expensive or free product!

Examining all relevant legal cases about this topic (releasing FLOSS when there is an existing proprietary product) would be daunting; I don’t pretend to have done that analysis. (If someone has done it, please tell me!) However, I think Charles River Bridge v. Warren Bridge can at least shed some light and is interesting to think about. After all, this is a major Supreme Court decision, so the ruling should be able to help us think about the issue of the government enabling a free service that competes with an existing business. In this case, the government knowingly created a competing free service, and as a result an existing business would no longer be able to make money from something it did have rights to. There were a lot of people who had bought stock in the first company, for a lot of money, and those stock holders expected to reap massive returns from their monopoly on an important local service. There were also a lot of ordinary citizens who were unhappy about this local monopoly, and wanted to get rid of the monopoly. There is another interesting similarity between the bridge case and the release of FLOSS: the government did not try to take away the existing bridge, instead, they enabled the re-development of a competing bridge. While it’s not the last word, this case about bridges can (I think) help us think about whether governments can release FLOSS if there’s already a proprietary program that does the same thing.

I would certainly agree that governments shouldn’t perform an action with the sole or primary purpose of putting a company out of business. But when governments release FLOSS they usually are not trying to put a proprietary company out of business as their primary purpose. In the case of Charles River Bridge vs. Warren Bridge, the government took action not because it wanted to put a company out of business, but because it wanted to help the public (in this case, by reducing use costs for key infrastructure). At least in this case, the Supreme Court clearly decided that a government can do something even if it hurts the profitability of some business. If they had ruled otherwise, government would be completely hamstrung; almost all government actions help someone and harm someone else. The point should be that the government should be trying to aid the community as a whole.

I think a reasonable take-away message from this case is that government should focus on the rights, happiness, and well-being of the community as a whole, even if some specific group would make less money — and that helping the community may involve making some goods or services (like FLOSS!) available at no cost.

path: /oss | Current Weblog | permanent link to this entry

FLOSS Weekly: FLOSS in the DoD

FLOSS Weekly #160 is out, and it features me! It’s an interview of me by Randal Schwartz and Simon Phipps about free/libre/open source software (FLOSS) and the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD). The DoD uses and releases FLOSS, and it has a recent policy about FLOSS that I think is pretty good. If you’re interested in this topic, take a look!

If you’re interested in this topic, you might also be interested in:

So take a look at FLOSS Weekly #160, and enjoy.

path: /oss | Current Weblog | permanent link to this entry

Intellectual Rights, not Intellectual Property

I think the phrase “intellectual property” is a misleading and dangerous phrase. Our entire economy is moving towards being a “knowledge economy”, but the term “intellectual property” misleads people into exactly the wrong understanding. Instead, use terms such as “intellectual rights”.

Not convinced? Not sure what I mean? Take a look at Intellectual Rights, not Intellectual Property.

path: /oss | Current Weblog | permanent link to this entry

U.S. Government Rules for Releasing Open Source Software (OSS)

A previous blog article announced that the January 2011 issue of the “DACS Software Tech News” (Volume 14 Number 1) is finally available. It was available in PDF form, but a few articles weren’t available in HTML form. Since that time the rest of the articles have been released as HTML (yay!).

In particular, my article “Publicly Releasing Open Source Software Developed for the U.S. Government” is finally available in HTML (it has a complicated table, which is probably why it took a while to release as HTML). That article summarizes “when the U.S. federal government or its contractors may publicly release, as open source software (OSS), software developed with government funds”. Even if you don’t work for the government or its contractors, you may still want this information, because you may want software that they’ve developed. All too often the government and its contractors don’t know what they can do (or not do).. so if you want them to release software as OSS, so you may need this information to help them determine if they can release it as OSS. But if you need the information in this article, you really need it, and I think a lot of people need it. That article is the result of a lot of work, and I thought it’d be useful to give some background about this article.

But first — why bother? This is important because the U.S. federal government and its contractors spend billions of dollars developing and maintaining software. I believe that often these could be more efficiently developed and maintained by releasing the software as open source software (OSS) and doing collaborative development. Besides, if “we the people” paid to have software developed, shouldn’t “we the people” get it? Currently, when “we the people” pay to develop software, we normally don’t get it, and that is senseless. It’s especially horrific in the research world. Often the government pays to develop software as part of research, but instead of releasing that software to everyone who paid for it (the taxpayers), it’s given exclusively to one organization. As a result, different researchers must constantly re-develop software to do further research. I think this absurd research strategy is starting to threaten U.S. competitiveness.

There are many people interested in releasing software as OSS, both in the government and in its contractors. But over the years many of them have told me that they couldn’t figure out what the legal rules were. For example, when I gave a webinar about open source software back in 2008, I was asked a lot of questions about when the government or contractors could release software as OSS. When I heard these questions, I figured that it’d be easy to answer — just read the contracts. But that’s not simple at all. A typical U.S. federal government contract is actually a huge document; just finding the relevant text is hard if you’re not an expert (you have to look for the “data rights” sections in particular). Once you find it, it’s hard to understand what the text means, even if you’re a lawyer… and most of the people who need to understand this are not lawyers.

So I began polling one lawyer after another, asking them to explain things. I then refined my summaries, and went on to others saying, “this is my understanding — do I have it right?” One thing that became clear right away is that there are a lot of sub-specialties in law. In particular, lawyers who understood the Department of Defense (DoD) contracting rules often didn’t know the rules for the rest of the federal government, and vice versa. My thanks to all the lawyers who helped clarify things, including those in CENDI! Some lawyers honestly didn’t know, even if they specialized in intellectual rights, which just goes to show how complicated this is.

I then summarized this into a set of slides, but they were still complicated. Gunnar Hellekson said that he liked the information I had gathered, but he thought my presentation was too complicated (he was right). Gunnar then tried to create a graph that simplified things, and showed it to me. I thought his graph was also too complicated, and in many cases wrong. Also, his graph made it hard to see how the different circumstances were the same and how they were different. But his work clearly showed a need to simplify things.

Gunnar and I then chatted during the August 2010 Mil-OSS conference in Arlington, VA, about how to make this simpler. The primary complication is that the copyright-related rights were hard to explain. So I decided to turn this into a big “if.. then…” table, where the conditions were on the left, and the “then” (what government and contractors are allowed to do) on the right. Gunnar gave me few more comments, and I then showed an early draft at the Mil-OSS unconference (where 30 people saw it and gave feedback on it). It was a complicated 2-page table to create, but it’s really easy to use, and that’s what matters. What I presented wasn’t “new information” — in theory this was already public information — but making information understandable is really important too.

I give this tale to show that this material, like many materials, was developed in a collaborative way, just like most open source software. I wrote the actual text itself, which is why my name is on it, but I received and responded to a lot of collaborative comments, and I thank everyone who gave me feedback. It’s not formal legal advice. But it’s impossible to follow the law or contracts if you don’t have a basic understanding of them; my hope is that it gives non-lawyers (and some lawyers) an understanding of the basics.

As I gathered this information, I was surprised to learn how often the government and/or contractors can release OSS when the government pays for software development. Often, the biggest problem with OSS release today is that the government and contractors simply don’t know what they can do. Of course, even if the government or contractors can do something, and know it, that doesn’t mean they’ll do it. Sometimes they shouldn’t release software as OSS, for example, software that gives a weapon system special capabilities over others’ should probably not be released as OSS. But often software doesn’t give an organization a special capability. Instead, all too often there are perverse incentives, encouraging government and contractors to do things that are not in society’s interest. But even if there are perverse incentives, the first step towards fixing them is to learn what the current rules are. The article helps government employees and contractors figure those out in many cases, and that’s useful too. Even if you have a special case not well covered in the article, it’s still useful to understand the “normal case”. Besides, if you want to change the system, typically you must first know where it is now.

If you read the article you’ll notice that I intentionally use the term “intellectual rights”, not “intellectual property”. I think the phrase “intellectual property” is a misleading and dangerous phrase; see my essay Intellectual Rights, not Intellectual Property for more information. (I’ll post separately about that topic.)

So anyway, please take a look at “Publicly Releasing Open Source Software Developed for the U.S. Government” or the January 2011 issue of the “DACS Software Tech News” (Volume 14 Number 1) and enjoy!

path: /oss | Current Weblog | permanent link to this entry

DACS Software Tech News: Open Source Software

The January 2011 issue of the “DACS Software Tech News” (Volume 14 Number 1) is finally available! The entire issue is dedicated to covering the relationship of the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) and open source software (OSS). If you’re interested in the DoD and software, the U.S. government and software, or open source software, you really need to look at this. Even if you’re not a U.S. citizen, you’re probably influenced by the decisions of the U.S. government (it spends a lot of money on software!), and the experiences and lessons it learns are probably useful in many other places. You have to register (sorry!), but it’s well worth it.

I wrote or co-wrote several of the articles, so please let me point out a couple of interesting points in them.

“Software is a Renewable Military Resource” notes that it’s possible for projects inside the government to use collaborative development approaches, even if the software isn’t released to the public; we call these “Open Government Off-the-shelf” (OGOTS) projects. Another term used for these projects is Government Off-the-Shelf (GOSS); people I respect use the term “GOSS”, but I worry that the GOSS term is confusing (GOSS isn’t OSS, because GOSS projects don’t allow arbitrary use and redistribution). In the DoD, a related term is “Open Technology Development” (OTD), which describes a community-based development process, be it OGOTS or OSS with community-based maintenance. The article has a nice little graphic that I think makes this pretty clear.

My article “Open Source Software Is Commercial” won’t surprise anyone who’s seen my already-posted article Free-Libre / Open Source Software (FLOSS) is Commercial Software. Basically, OSS is commercial software. Anyone who says nonsense phrases like “commercial or open source software” probably doesn’t understand open source software, and is unlikely to make good decisions about software. This new article focuses more on the formal legal definitions.

My article “Publicly Releasing Open Source Software Developed for the U.S. Government” summarizes “when the U.S. federal government or its contractors may publicly release, as open source software (OSS), software developed with government funds”. If you ever interact with the U.S. federal government or its contractors in software issues, make sure they get a copy of this article. It’s easy to say “follow the rules” and “obey the contract” but it’s often impossible to find out what the rules and contracts actually say. Even many lawyers didn’t know the information in this article, and this is the kind of information that many non-lawyers need to know. All too often the government and its contractors should be releasing software as OSS, but don’t know that they have the right to do so. It’s taken me years to pull together this information. The article gives 5 basic questions that you need to answer. One of those questions — “Do you have the necessary copyright-related rights?” — has a supporting table that I’m really happy with. That table manages to take a lot of complicated legal mumbo jumbo and turn it into something that can be actually understood. One point this article brings home is that using the term “intellectual property” is grossly misleading; in government contracting (and in many other circumstances) it usually doesn’t matter who holds the copyright; what matters is who has what rights. Anyway, if you need this information, you need this article.

Anyway, here’s the full list of articles in this issue:

So please, take a look at January 2011 issue of the “DACS Software Tech News” (Volume 14 Number 1).

Full disclosure: I’m on the DACS Software Tech News board (as a volunteer; nobody pays me). But the issue is good anyway :-).

path: /oss | Current Weblog | permanent link to this entry